European contemporary dance at the crossroads of the past and the contemporary era

Hyeongbin Cho (dance critic)

Among numerous performance art festivals in Europe, several held in summer focus on dance. They are Montpellier Danse, held from late June to early July in Montpellier in south of France, Impulstanz, held for a month from early July to early August in Vienna, Austria, and Avignon Festival, held during July in Avignon, the French city renowned for its festivals. These festivals all center around performance art and are important sites in which contemporary state of European dance can be examined. I visited various European countries during July in the heat of summer 2023, observing the dance festivals as an outsider and spectator, in order to examine where the European contemporary art is today and where it is headed to.

Montpellier Danse: Memory and Creation

In Montpellier, a city that faces the Mediterranean, the summer dance festival Montpellier Danse is held every year. In its forty-third year, the festival is directed by Jean-Paul Montanari—it is working to imbue the art of dance in various places in Montpellier. As can be gleaned from the opening statement by the critic Angès Izrine—“Mémoire et création (memory and creation)”—Montpellier Danse this year seems to have focused on the questions arising from the crossing of the past and present. While it is not uncommon to feature masterpieces from the past in today’s festivals, this year’s Montpellier Danse featured today’s choreographers who reworked the pieces featured in past years’ performances, which represents an attempt to show how the “vainful” (dance) pieces that cannot be the same as the past performances on stage are “created” (in the past and today).

Boris Charmatz, the choreographer who was appointed as the new director of Tanztheater Wuppertal in 2022, presented two performances in addition to Palermo Palermo (1989), which was originally performed by Tanztheater Wuppertal. In particular, À bras-le-corps (1993) is an early work of the choreographer, choreographed and performed in collaboration with another choreographer, Dimitri Chamblas. The contact, embrace, and sticky encounters of the two men in close quarters made the audience carefully remember the bodily objectives the two artists in their late teens strived toward thirty years ago. With other choreographers’ recreation of Dominique Bagouet’s 1984 performance Déserts d’amour in the closing show performance, Charmatz’s performance brought their past movements to the present and recreated it with bodies that are thirty years older, adding to the experience of Montpellier Danse’s theme that considers the crossroads of the past and present.

Montpellier Danse also has consistently supported creative efforts, with many performances premiering in the festival. Among them, Majorettes (2023) by Michaël Phelippeau was a performance that discussed the traces of body and life under the unique theme of cheerleading. Majorettes, meaning “cheerleaders” in French, features the cheerleaders of Montpellier who were organized in 1964. The performance uses the physical rules and bodily methods from cheerleading, displaying the choreographic codes and the lives of the individual cheerleaders, who are women in their sixties today. While the performers drop the staff and make repeated mistakes, these “gaps” in the choreography disperse the tight nature of cheerleading, and makes the audience think about what the elderly body does to our present understanding of cheerleading as it recreates the physical regulation.

The festival has a close relationship with the region and has given birth to many choreographers, it also summarizes diverse ideals of concurrent dance movements by featuring numerous performances from overseas. Dana Michel, a Canadian choreographer who had already participated in Montpellier Danse in 2019, brought Mike (2023) to the festival this year. Rather than performing in the closed space of a theater stage, this performance chose an open studio, as well as the surrounding lobby, balcony, and garden spaces to allow the audience to freely wander and view the performances.Dana Michel invites the audience to pick up various objets scattered around in the spaces, question the methodology of performance art, as well as think about the process and role of audiences to whom the private narratives and acts are delivered.

Impulstanz: The Past Lives On

After Montpellier Danse concluded in early July, I travelled to Austria to Impulstanz, the international dance festival held in Vienna from July 6 to August 6 this year. Impulstanz is in its fortieth year after it began as a collection of small workshops in 1984. today, the massive festival is celebrated in the bustling metropolis of Vienna. This year, sixty-eight performances from twenty-four countries were featured in various theaters in downtown Vienna. In addition to Volkstheater, the hub of Impulstanz, and MuseumsQuartier Wien, the downtown museum quarter, various theaters in the city were filled with Impulstanz performances for the entire month.

I was happy to see the performances of choreographers whose work I saw in Montpellier Danse. Boris Charmatz, whose various performances were featured in Montpellier Danse, participated in Impulstanz with SOMNOLE (2021), another solo piece. In this performance, the dancer’s unbroken whistling from the beginning to the end is the only sound that can be heard during the show. As several popular songs continue through whistling, the performance showed with the body the ambiguous state between sleep and insomnia. This show was performed by Terrain, a group formed by Boris Charmatz to engage in his personal work, exhibited a different grain of bodily movement than seen in his other performances, making the audience think about the presence and existence of the body.

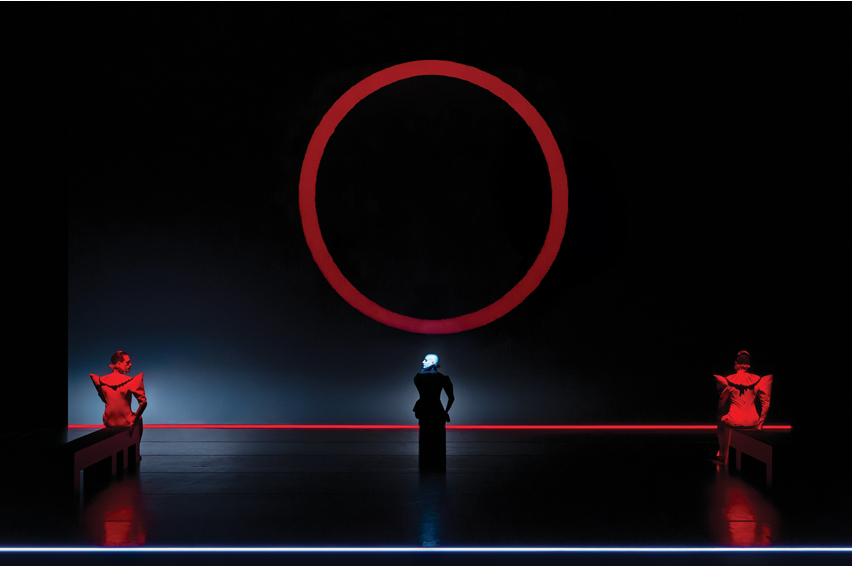

The most emphasized performance during the first half of this year’s Impulstanz must have been those by Lucinda Childs. Childs, who was active in Judson Dance Theater in the mid-twentieth century, is a master of contemporary dance, and she has broadened her horizon by collaborating with the director Robert Wilson. RELATIVE CALM (2022), which she featured in Impulstanz this year, was created by the two artists during the Covid-19 pandemic as they quarantined at home and solidified their past performances. This performance’s highlight was the unique directing style of Robert Wilson. The visually imposing stage design, simple and repetitive sounds, and the fitting minimal movements constituted an excellent direction that the audience expected from the collaboration of two masters.

mpulstanz was also a place which exhibited how and what concurrent dance experiments and transforms. ONE SHOT (2016), created together by Meg Stuart and Mark Tompkins and performed by the two, was an interesting show that displayed a way to create a performance through improvisation. Set rules were not simply expressed in an improvised manner on stage, but rather, the performers improvised situations on stage and discussed those circumstances to improvise the structure of the performance itself on sage. Thus, the design of the show itself was deconstructed through improvisation.

Concurrent Temporal Nature of the Past

Other than showing respect for the performance and the artistic world of old choreographers, what does it mean to summon the past to the present? That is achieved by preserving the past performance of Pina Bausch and recreating it in the present, but the endeavor can be executed by performers who are thirty years older re-conducting the old choreography with their present bodies, observing the cracks and creaks that result. Lucinda Childs’s performance feels refreshing because her style maintains the minimalism that she introduced in her postmodern dance pieces, which in turn creates discord and misalignment with the present in 2023, thus generating a potential for certain new meanings.

In Europe, where it is possible for choreographers to visit various festivals to showcase their work during a season, it is certainly not awkward to see re-choreographed or re-performed shows from the past. This is because it is important for both festivals and choreographers to have continued submissions from choreographers with long history with the festival or has grown with the festival. However, a challenge that cannot be overlooked is to examine the meaning of re-summoned past performances, to see their meaning in the concurrent temporal nature. Through the various European dance festivals that attempted to bring new meaning to the present by disrupting the past, I came to think about the temporal place of korean dance. By identifying the present and considering what past can influence it, as well as attaining the concurrent temporal nature—that is a direction of dance performance art that the European dance festivals are trying to provide.

PREV

PREV

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)