Performance Info

Artist Seo Hyun-suk studied film theory in the United States and with an interest in theater and performance, has been directing performances since 2004. Since 2010, he’s been investigating how to fully access audience’s private emotions and has been creating site-specific works. His major works include Heterotopia (Seun Sangga, 2010), The Divine Prostitution of the Soul (Yeongdeungpo 2011), Heterochrony (Culture Station Seoul 284, 2012), and The Angel Tenuously Named, (Namsan Arts Center, 2017).

Q. As a video artist and having worked on performance pieces, tell us how you became interested in performance language.

A. I have been interested in theater since college. When I was studying video art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I acted in theater as well. After I returned to Korea and was feeling lost while working on video projects, I watched many performances, and I began working on projects that I thought audiences would be interested in watching. In 2010, I watched a number of performances that I found moving; in particular, Romeo Castellucci’s and Jerome Bel’s works had a big impact on me. Hidden in their works were questions—What is theater? What is dance? In some ways, they were old modernist questions, but I found works that were formulated with those questions in mind and had the ability to communicate with the audience fascinating. Afterwards, I began creating works in a manner that conversed with the works that had affected me.

Q. Your site-specific works take the audience on an unfamiliar journey. Could you tell us how you came to that format? Also, in many of your works, Seun Sangga is a central element. Could you tell us the significance of the site?

A. When I first started, I didn’t have any grandiose plans about creating a new format. When I came back to Korea in 1998, I once got lost while walking around the Sinchon area. It was completely different back then and there were a lot of fortuneteller places. There were narrow alleyways that tangled, and the area had a very special feeling of the old days. I have a special affinity for alleyways because I grew up around them as a kid. They were like a maze, and you were able to experience something that you couldn’t on the main roads where cars passed through. Seoul was changing very rapidly and it was quite something to see an area that seemed to be preserved as if it were in a time capsule. I wanted to create something experiential, but then some time passed and a Megabox movie theater came in and everything changed there. I thought if I waited any longer there wouldn’t be any place left that looked like it were in a time capsule, so I started to aggressively look for an area and found Ip Jeongdong. It was a place where you could invoke the past as if you were in a time machine. I didn’t know at the time that Seun Sangga was designed by the architect Kim Swoo-geun. It was a place where you could buy pirated music in the 80s and a place where censorship didn’t exist; it was like a rabbit hole. When I visited Seun Sangga with these memories, I started to see things I hadn’t seen before. The sense that it was a building that was lagging behind the times was strong, and when I went inside I saw something architecturally extraordinary. Kim Swoo-geun’s vision had been preserved. I thought it was incredible that his vision of the future from the 60s overlapped with the surrounding area, which was lagging behind. I started going there frequently and thought I have to create something. I thought it was cool to go outside of the theater format, and I strolled Seun Sangga alone and went through unfamiliar experiences. So I ended up making a project that allowed audiences to experience what I had experienced alone. I put on Heterotopia in 2010, 2011. It was a site-specific work that took place in Seun Sangga. At the suggestion of the architect Jo Min-seok, who attended a performance as an audience member, I began making a documentary about Seun Sangga. I produced a documentary about a North Korean architect and held dual video exhibitions at the 2014 Venice Biennale of Architecture, and exhibited the completed documentary about Seun Sangga at the 2018 Gwangju Biennale. Seun Sangga questions what art is. It wasn’t the intention of the architect, but ultimately Seun Sangga functioned as an important cultural platform. You could say it was a failed utopia or failed modernism. As not just Korea but Asia came out of a colonized era and put war behind it, it tried to transform itself, as did this building, and the building was able to have an important role in art. Although we’ve come a long way from the clashing of the instability of circumstances and the military regime, and the clashing of economic hardships and the rapid growth of capitalism, we didn’t get to achieve the changes of the future. This was the difficult conclusion I had arrived at from the last eight to nine years of putting on Heterotopia with Seun Sangga at the center.

Q. Your performance pieces have the performers and the audience as oneon-one entities. What method did you use to construct the space and facilitate the meeting of the audience and actors?

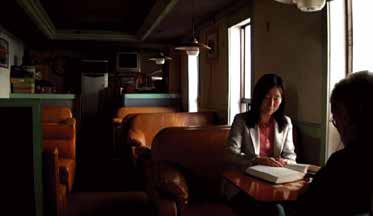

A. When I was in high school, I went to see a play where I was the only audience member. It was a solo performance, and because I was the only one in the audience, it felt strange and it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between the play and reality. More interestingly, since I was the only person sitting in a big theater, it was not only uncomfortable but the whole theater felt strange. I wanted to create a work in which the audience could experience that same feeling. In Heterotopia each audience member walked around alone, but there were performers placed in various points, such as a guide or a performer passing by on a bicycle. The audience members and performers didn’t actually meet and talk, but I wanted to further develop this format. I did The Divine Prostitution of the Soul and Heterochrony at Seoul Station. I wanted to do a play in which one actor and one audience member meet one-onone, and I was curious about what would happen and the audience member’s response in a play setting and not so much a site-specific work. Instead of the audience member following a performer acting as a guide through a specific site, I wanted to see how the audience member would react to a performer within the format of a play. I put on a play at the Nam June Paik Art Center, where thirty audience members and thirty performers took a stroll through a forest and conversed, and I was very surprised at the level of personal stories the audience members divulged. It was either because people were more inclined to share with strangers or because they knew that they would never see one another again, but I became curious about how the intimacy had arisen and how far I could push that intimacy within the confines of a play, and I wanted to see how it would be different from the realities of the everyday. The Divine Prostitution of the Soul was performed in Yeongdeungpo, which used to be famous for prostitutes. It has changed a bit, but if you go inside the market, the alleyways still remain and the shabby inns can still be seen. I didn’t bring in the element of prostitution myself; I got it from the title of Baudelaire’s poem. Baudelaire wondered how much was shared when people passed each other on a busy street, and theatrics while people passed a complete stranger, imagining each other’s lives and sometimes wearing masks and forgoing their identities. This was an important experience in a modern city and it was what Baudelaire called the prostitution of the soul. That you meet a stranger with your soul. I found that incredibly theatrical. It’s looking at your life from the perspective of another person. It means to imagine what it would be like living the life of another person. You could say it’s training for a thespian, and I brought that idea to the one-on-one meetings between the audience members and performers. If you had an intimate conversation with an audience member, how much of it was theater and how much of it was your soul, and if your inner self is your soul, could that be compromised? I was interested to see if the boundaries could change and if controlling the levels of the boundaries is what makes theater or not. I started it as a site-specific project but I thought I should bring in the element of theater, which would be the important foundation of the project.

Q. In regard to bringing in the theatrical element it seems like you actively seek empty spaces or apply a character of the theater in your work. Could you tell us a bit about that?

A. Beginning with The Divine Prostitution of the Soul, I started using empty theaters. I found a place in Yeongdeungpo, and the starting point was a wedding hall. It was a place where people sat facing the same direction; you could say its structure was the same as a theater. An audience member and performer would meet at the wedding hall one-on-one, and afterwards they would go to a market and walk through an alleyway, stop at a fortuneteller, and then go to the final destination, an adult movie theater. They would sit and watch a movie I had made about what the audience member had just experienced, as if it were a flashback, and the performer would disappear. I wanted to experiment with the concept that a kind of theatrical contract is made and how much the place determines the relationship, and how much one lets go. At Seoul Station, I used a theater nearby; there wasn’t a stage, so I couldn’t fully use the space, but I made a small stage to put in context that the audience member and the performer take off from the theatrical stage. I put this on in Japan as well, where it was also a one-on-one performance, and I chose a space that had a theatrical stage as the final destination. One place was a wedding hall, which was used to rehearse plays, but it still had the structure of the wedding hall. Another place was a racetrack, but there were no horses or races; it was a place where you would watch races taking place on other racetracks on monitors, but it looked like a theater to me. I wanted to incorporate the way two people enter the place, and the act of sitting and watching and having the performer next to the audience member as his or her partner and having the performer and audience member enter a theatrical relationship contract. Using what was once a wedding hall in Japan, we applied the subject of marriage, setting it up as a fake marriage or as if reuniting with an old partner as one’s last memory of life, and had the audience member and performer meet and take a wedding-like vow as a metaphor of a kind of theatrical contract. I wanted to make it clear that the actor would appear and any intimacy or personal sharing would be happening within the theatrical contract as if it were unfolding on stage. In that sense, the theater space was extremely important.

Q. You previously used spaces that were like theaters, but recently you have been using actual theaters where plays are held. Please tell us about The Angel Tenuously Named.

A. As I was working, I wanted to use an actual theater, and Namsan Art Center gave me that opportunity. I love an empty theater and like just sitting in an empty theater. I use the subject of an angel, but it’s not that an angel magically appears; I wanted to connect it to the story I told in Seun Sangga, that utopia is not coming. We keep waiting, but what we have left is only ruin; the idealistic utopia is getting further away from us as we move forward to the future. That is why it is called The Angel Tenuously Named.

It was important that the audience members experienced sitting alone in an empty theater, and I thought I needed to have them move around. When I was in America there was an opera theater that had closed; it was a huge mazelike space, and I remember losing my way and being scared. It wasn’t fear like a ghost could appear, but as if I had lost the existence of the time I had possessed, and I wondered if I felt that way because it was a theater. A completely empty theater, it certainly existed, and I couldn’t see the theater, but when I would enter a room there was a feeling of unconsciousness. If the stage could be compared to being a space of consciousness, even though I couldn’t see it, there was an empty theater inside my head somewhere, and it was there in actuality right next to me, and it was so interesting to have communication with a starkly empty stage inside my head. It’s a special experience to walk around an empty theater alone. If the stage was something that had consciousness, I wanted to bring to life the feeling of unconsciousness, and I thought if you were to go into a space of unconsciousness it would be good if a child could guide you.

Q. In The Angel Tenuously Named, you use VR. You’ve used other tools in the past to make things more interesting for the audience. Could you tell us why you used VR this time?

A. At Seun Sangga, in Heterotopia, I used a Sony Cassette Walkman. Cassette tapes are an old technology, and I thought it was appropriate to connect it to Seun Sangga, so I used it. Back then I used equipment and tools that I had made myself, but VR is different. I can’t record it myself, so I had to leave it entirely up to the director of photography, and at first I was nervous. Despite that, I used VR because it was important to experience everything, starting from Seun Sangga, in a non-stage everyday space and reality, touching real objects that aren’t from a movie or a directed mise-en scene and experiencing with all the senses, like smell and touch. I think the difference between reality and fiction can be fluid. If you press the record button on a Walkman the surrounding sounds can be heard in real time, but because it’s not in stereo there is no sense of direction. The sounds you hear through a machine lack a sense of reality, but the surround sounds come through in-between the sounds. It’s a mechanical reality that you can’t call reality. The Seun Sangga project can be called a site-specific performance, but I may have worked on it unconsciously thinking of it as a movie. One audience member expressed that my project was like a “film that came out of a broken camera.” I thought if you wake up from a film matrix you don’t return to reality, but maybe you continue to experience within the matrix. Differentiating between what we think is reality and directed space that is mediated as fiction might be dichotomous, but once I separated them, there was an interesting possibility of the two clashing. That’s why I think I used VR. To make that space between VR and the complete opposite even more strange. When you collide with the fake world of VR, then the difference is even bigger. You might not have seen the space as real, but then you wear the VR headset and view the space. When you take off the headset, the space can seem even more real than before or you might experience the complete opposite. The space was definitely fiction with VR, but it could have felt more fake without it. These tools further highlight the properties present at the site and give way to questions, and I think about how to deal with these mediated aspects.

Q. I’m curious what questions you have today as an artist and your future plans.

A. I’m making a documentary to archive Asia’s modernism architecture. I finished the part about Seun Sangga this year, and plan on including Sri Lankan, Cambodian, and Japanese architecture to finish the project by 2020. This project looks at under what circumstances Asia’s modernism began, how it interacted with political situations to form modern nations, and what kind of role architecture and art had in the nations coming out of the colonized era. After meeting Asia’s architecture historians, I realized how difficult it is to restore even one or two past generations in today’s context. This is a personal subject, but as I have matured I have become interested in art from the 1960s, when avant-garde art was at the forefront. Avantgarde art from the 60s was a resistance culture against a kind of hegemonic culture; there was a question of how a subculture that started as art could change society, and today, we don’t even come across that question, not even in films. My homework is to see how effective today’s worn concept of artistic revolution is. It’s overwhelming to develop an idea for a project from such a personal standpoint, but as someone who theorizes, I have to question how art connects to my work; how my projects can pose valid questions for this era; how I can create new developments that are not just theory; and how my way of communicating with the audience changes. Also, could a new art form be born? And if yes, what would that be? These are the questions I have.

Photograph Copyright :

1. (Main Image) Heterotopia ©Seo Hyun-suk

2. Heterotopia ©Seo Hyun-suk

3. Heterotopia ©Seo Hyun-suk

4. The Divine Prostitution of the Soul ©Seo Hyun-suk

5. The Divine Prostitution of the Soul ©Seo Hyun-suk

Production Details

- Director

Reference

- E-maillucida@yonsei.ac.kr

.jpg)

.jpg)

PREV

PREV

.jpeg)

.jpg)

_(c)포스(FORCE).jpg)

_(c)장석현_코끼리들이 웃는다(SUKHYUN JANG_ELEPHANTS LAUGH).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(c)한받(Hahn Vad).jpg)

_(c)비주얼씨어터 꽃(CCOT)(1).jpg)

_(c)봉앤줄 (BONGnJOULE)(1).jpg)

_(c)대한민국연극제 2019 (Korea Theater Festival 2019)(0).jpg)

_(c)몸꼴(Momggol)(1).jpg)

2018MODAFE_Taemin Cho (2).jpg)